Story Design - Story Telling pt.2

Friday, July 1, 2011 at 9:03PM

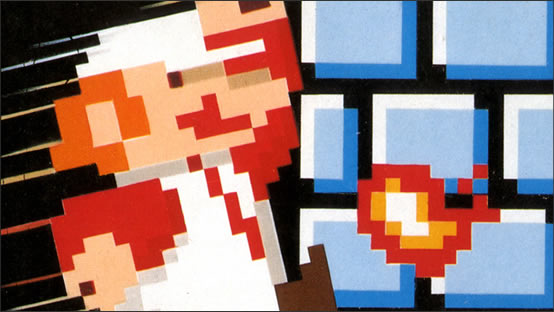

Friday, July 1, 2011 at 9:03PM Let's start with the example that I always turn to on this blog; Super Mario Brothers for the NES. Often, people dismiss this game for having no story. This stance is just ignorant. Others claim that there is a story, but it's flimsy and barely there to give the gameplay a bit of context. It doesn't say much to call Mario's story flimsy. Whether you like it or not, it's better to offer a detailed explanation of its parts and how they work together. Let's use the CED system.

Super Mario Brothers's story content is pretty straightforward adding up to a fairly simple story. Set in the Mushroom Kingdom, players travel through land, sea, air, and castles (setting). Mario, Bowser, Peach, the toads, and all the enemies take on flat, familiar roles like hero, villain, citizen, and damsel (characters). The theme is adventuring, rescue, and bravery. And the plot is focused on action platforming where beating one level flows into the next and the next until Mario makes his way to World 8-4.

The execution is more complicated. With little text in the game, the vast majority of the content is conveyed through visuals and gameplay. All non-playable scenes are seconds long keeping the focus on the gameplay. Due to the simplicity, SMB doesn't have a problem being efficient and coherent. After all, "but our princess is in another castle" is the most complex statement in the game. The pacing is generally designed around 8 waves of increasing difficulty. One wave per world presented in 4 level groups. Yet in this ludonarrative structure, there's significant variation. Not only are there alternate paths through many levels in the game, but there are warps that can alter the progression further. One player may get through the game in a few minutes by skipping most of the levels in the game. Another may take the long route by playing through all 32 levels.

As for the Super Mario Brothers Discourse, at the time of its release there was no other video game like it. So, it definitely scores points for creativity. Back in the 1980's it was the norm for video games stories to start inside the instruction manuals. You can decide for yourself if you consider Mario's instruction manual story as part of the game or simply a part of the product. If you think it's not part of the game, then does the external text count as a transmedia element. Read the instruction manual here. I've pulled out the best part below.

One day the kingdom of the peaceful mushroom people was invaded by the Koopa, a tribe of turtles famous for their black magic. The quiet, peace-loving Mushroom People were turned into mere stones, bricks and even field horse-hair plants, and the Mushroom Kingdom fell into ruin.

The only one who can undo the magic spell on the Mushroom People and return them to their normal selves is the Princess Toadstool, the daughter of the Mushroom King. Unfortunately, she is presently in the hands of the great Koopa turtle king.

Mario, the hero of the story (maybe) hears about the Mushroom People's plight and sets out on a quest to free the Mushroom Princess from the evil Koopa and restore the fallen kingdom of the Mushroom People.

You are Mario! It's up to you to save the Mushroom People from the black magic of the Koopa!

Ultimately, Super Mario Brothers delivers a relatively simple story at a high level of precision because the telling focuses on conveying information the best ways video games can; gameplay (interactivity) and then visuals. It also helps that the gameplay is excellent. For those who dismiss Mario's story, I argue that it's impossible to enjoy the gameplay and not appreciate the story. Put simply, the actions of getting Mario from 1-1 to 8-4 is the story and gameplay simultaneously.

So when you want to talk about a story overall, because even simple stories like Mario's are so complex and multi-faceted, there's really no substitute for a comprehensive description like I just made. If you're not in the mood to do all the work, your analysis should at least touch on all of the content and execution facets. If you're not prepared to make such an analysis, then focusing on a facet or two will produce better results. Just be sure not to claim or imply that your statements cover the whole story.

More Examples

The following is a list of video games that are notable for the following qualities.

Content

Setting. Many games are set in interesting worlds or locations. Remember, the Gameboy version of Tetris is set in Russia. For the purpose of story analysis we must be careful to look for examples that are well crafted as opposed to being just unique. The creativity category is a different matter that falls under the discourse category. BioShock, Portal, and the Grand Theft Auto series are a few popular examples of games where the setting is rich and integrated into other parts of the narrative and gameplay. Other good examples include Advance Wars: Days of Ruin, Shadow of the Colossus, and most of the games in Zelda series. In fact, it's hard to mess up a setting. When it works we tend to notice. When there's not much there, we tend to look to other elements of the story.

Characters. Characterization can be more complex in video games than in any other medium. In addition to various character types (flat, round, psychologically rich, etc), there are new perspective and emergent issues to consider. Game characters can either be non-playable or playable. Whether by a little or a lot, player interactivity opens up characterization in new ways. Is Commander Shepard in Mass Effect a paragon or a renegade? Is he both? Yes, it depends on player choices, but what does that mean for our analysis? Do we consider the entire range? Is that possible? Do we pick an interpretation and focus on it?

The variable and player determined character isn't always a problem for the main character of the game. There are extreme examples like RO9 where players control 9 characters at once and Poto & Cabenga for 2 at once. Then there are more common examples like taking control of multiple characters one at a time like in Zelda: Phantom Hourglass, Zelda Spirit Tracks, the Advance Wars series, and the Professor Layton series.

As much as I love round characters with complex psychologies like GlaDos (Portal 1 & 2) and Linebeck (Phantom Hourglass), I also love the flat characters like Mario, Link, Donkey Kong, and the Prince (Katamari). Great stories can feature any combination of character types.

Plot. Stories are a series of events in place and time and they feature characters (or something like characters). Events are made of actions as simple as surviving to supernatural combat. Along with considerations of how events connect together, which can be quite complex due to non-linearity, we have to consider how the plot grows, climaxes, and resolves for both the gameplay and the story content simultaneously. RPGs like Final Fantasy 6 do a great job weaving together many characters and events into an epic plot. The Zelda series is another great example that typically features a plot where little by little the child like Link fulfills the role of the courageous hero. Some plots are clear from start to finish like Shadow of the Colossus. If you need to kill 16 colossi to save the girl, then the death of each colossus leads right into the hunt for the next one.

Complexity/Simplicity. This facet needs little explanation. On the complex end there are games like Metal Gear Solid 4, Mass Effect, Animal Crossing, the Professor Layton Series, many games in the Zelda Series (Majora's Mask, Phantom Hourglass, etc.), many MMOs like WOW, and the Resident Evil series. All these games feature lots of characters, backstories, or other details. On the simplicity end of the spectrum are games like the Super Mario Brothers series, the Katamari series, Tetris Attack, BOXLIFE, Super Meat Boy, Donkey Kong Country Returns, Shadow of the Colossus, and many old school games including Sonic. The list goes on. There can be a lot of craft in a few details and little said in many.

Theme. No other facet of story content sits more closely to the core "meaning" and "about-ness" of a story than theme. Since the days of our gradeschool educations we've been taught to think about stories as communicating more than just simple events with characters. Uncovering the theme, (abstract, "big picture" ideas) is like finding that "ah-ha" Eureka moment. I know that without the theme that connects multiple facets of a story, some feel that such a story isn't worth much. Or without that "extra layer" of meaning, a story is merely a bunch of independent details. To me, this is a strange and limiting way of looking at the issue.

Once you realize that all culture is steeped in abstract ideas and how humans cannot help but imbue whatever they create with their culture, you'll see that any piece of art can be read for increasingly deeper meaning or commentary. Still, each of us carry our own biases and cultural lenses that make observing anything inherently complex. We naturally find patterns and we naturally see ourselves reflected in the world. We should worry about finding meaning, not where it comes from.

I'll list a few examples of games with obvious themes. Zelda Phantom Hourglass has themes of death, dreams/ambition, arrested development, and the transformative power of courage. Advance Wars: Days of Ruin features a struggle against utter desolation and themes of survival and humanity. Pokemon Black/White boldly introduces the themes of personal truths, personal choices, and a blended reality. Uncharted 2 plays with the theme of greed in the pursuit of treasure. Metroid Other M runs with themes of nature vs nurther and parenting roles. The Mario Galaxy series plays with the themes of loss, birth, and the forces that transend the universe.

In part 3 I'll give more examples of video games that illustrate the facets of execution and discourse.

Reader Comments (4)

I agree that theme is something that can be interpreted personally without authorial intention or design behind it (as in deriving meaning from a flower, life, air, art, etc.). What can be potentially frustrating though is when a game gives you a strong impression of a theme or builds up an experience, but then the theme(s) suddenly become inconsistent and incoherent with that experience.

I find this can often happen in commercial game development where there are many, many people driving the direction of a product (from the publishing level down to the developer level), all coming at things from different angles. It winds up creating somewhat of a schizophrenic production where the intended themes are diluted and even in conflict with what the game "story" and the game experience is purported to be "about".

But I suppose the products that result can still be viewed as having valid themes and meaning (I just personally tend to not gain fulfillment from them...) Shadow of the Colossus on the other hand... Now that was profound :)

-Kaz

@Kaz

So many people love Shadow of the Colossus. (Me too).

You're right about how big games can get stretched thin.

I tend to get frustrated the most with a story when it's set up so well and then it just throws it all away. How good of a story teller/creator do you have to be to do 80% great work and then throw it all away with 20% contradictory elements and poor execution?

"the actions of getting Mario from 1-1 to 8-4 is the story and gameplay simultaneously"

YES!! I can't tell you how often, as an English Lit student, I've had to contend with ignorant assumptions about video games that basically boil down to a prejudice against the idea that they can ever convey themes and tell stories as deep and meaningful as those found in literature and film. This article elaborates perfectly what I've always been trying to say to people who try and enforce a separation between gameplay and story.

The story of Super Mario Bros. is so often criticised that it's become an unquestioned consensus amongst gamers and non-gamers alike that its story is just plain 'bad', and the gameplay usually serves as recompense for the flimsy story. But as you wrote, the setting, plot, and characters, albeit simple, are well designed and executed. And if we can agree that SMB's plot follows the structure of an adventure or quest, then surely the game's well-designed enemies, levels, and difficulty curve are analogues of the threats, locales, and pacing found in adventure novels/movies.

Since video games are still a relatively new medium, I think people are still applying the same criteria and value scales by which they evaluate other media to video games and criticising games when their evaluative methods fall short rather than criticising their methods. I've read all of your Critical Gaming articles up to this point but this has been my favourite thus far because of the way you've applied narrative to video games without treating them like books. All the work you've done on this blog has helped me a lot with figuring out my own views on games criticism but I felt the need to comment here because this article is especially relevant to the kind of stuff I want to write. Thank you!!

Thanks @Bradley